A firm in a “pick and shovel” market produces a good or service that serves as an input to other businesses. A “frontier” pick-and-shovel supplier has made a significant technical breakthrough in applied science or engineering that has enabled capabilities in its product previously considered impractical, uneconomical, or impossible.

Pick-and-shovel markets have been around for centuries. Has anything changed much in recent years with firms such as Intel, Qualcomm, NVIDIA, and Amazon? To answer, let’s start with Samuel Brennan, the first West Coast entrepreneur to (literally) exploit the sale of a widely used pick or shovel. Like many West Coast billionaires today, Brennan was, shall we say, prominent but not popular.

Brennan owned two general stores, one in San Francisco and another in Sacramento. The latter gave him access to rumors of a gold discovery on the South Fork of the American River, which he confirmed for himself in the spring of 1848. In early May, Brennan walked through the streets of San Francisco with a vial of gold in his hand, shouting, “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!”

Brennan did not spread this news with charitable intent. He had spent the previous month buying up every available piece of mining equipment and related supplies. He resold them at exorbitant markups during the rush he created, reinvested the profits in real estate, and became the first West Coast millionaire.

Aside from legal restraints on unethical monopolization, the modern version of pick-and-shovel economics involves far less gold and much more silicon. Is there any other crucial difference?

Centralized

After being selected as the microprocessor supplier for the IBM personal computer (PC), Intel became the dominant producer of Central Processing Units (CPUs) for personal computers. Based on that experience, one might think that pick-and-shovel businesses are most effective at a large scale, supporting widely deployed products with many applications. After all, large-scale enables an organization to amortize fixed and sunk costs over a larger revenue base.

There is a grain of truth to that observation. Two other leading firms in integrated circuit design, Qualcomm and NVIDIA, also support widely deployed products with many applications. Qualcomm dominates chipsets for digital communications equipment. NVIDIA dominates the market for Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) in hyperscale data centers. They get similar economic benefits from scale, despite different end users and products.

Still, the scale came about through a combination of foresight, skill, and luck. Intel invested in frontier manufacturing and design. Yet, they ultimately needed IBM’s blessing. Qualcomm’s designs led to the invention of Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA). They ultimately required the cooperation of US carriers. NVIDIA survived years in the volatile gaming market. It ultimately needed growth in scientific computing (more on this below).

Once they got large, management used scale to maintain the lead. For example, after it began to lead the PC market, Intel was given the option to purchase frontier photolithography equipment earlier. NVIDIA gets a similar advantage through its partnership with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

Intel, Qualcomm, and NVIDIA all sell to new frontier markets with backward-compatible designs to guide buyers’ upgrade paths. If that is done well and on a large scale, then it prevents any potential rival from gaining the same advantages. Relatedly, scale can arise from selling a standard design that others build around, supporting a broad array of applications. All three of these firms take advantage of that, too.

Don’t get me wrong. There was nothing easy about building such partnerships and upgrading them without losing customers to rivals. Whole courses are devoted to studying such business strategies.

Transitions become particularly challenging with significant shifts in demand. For example, Intel shifted from desktops to laptops, and NVIDIA shifted from gaming to scientific computing. Still, it is easy for a leading firm to get focused on guiding users in its core business and subsequently lose sight of future growth opportunities. There are not enough managerial platitudes in my dictionary (nor space in this column) to describe, for example, the challenges Intel has faced in smartphone markets and developing chips with parallel processing.

Distributed

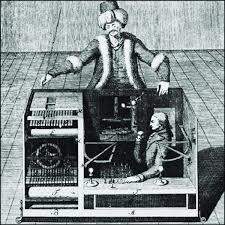

A different set of lessons about frontier picks and shovels comes from tracing the journey of a new service developed by Amazon. In this case, let’s focus on Mechanical Turk.

The story begins after the turn of the millennium, when Amazon faced an unavoidable headache. As it expanded the scope of its website to include a wide range of products, it faced a vexing product labeling problem. Amazon sought an automated method to resolve simple questions, such as whether “Sony 42-inch LCD TV” and “Sony Bravia KLV-42 HDTV” were the same product.

All such issues were resolved manually. An employee inspected, evaluated, and resolved the open question. Why manually? Because certain simple decisions—like matching, labeling, or verifying information—were trivial for humans but intractable for computers at scale.

Rather than build a massive data-entry workforce, Jeff Bezos and his team sought something he would later call “artificial artificial intelligence,” a system in which humans could perform small digital tasks that machines could not yet perform. This also required new technologies, including APIs and scalable interfaces, to handle large volumes of small-scale human microtasks, such as image object recognition, text transcription, and data verification.

Long story short, the internal service acquired a set of externally facing features. It emerged online in 2005. Stressing the magic of service, Amazon called it Mechanical Turk, and users referred to it as MTurk. MTurk matched users from anywhere on the Internet who needed microtasks requiring human labor with those who could provide them. It was anticipated that thousands of other organizations—researchers, startups, and developers—faced similar gaps between automation and human judgment.

From the buyer’s perspective, MTurk was a new kind of pick-and-shovel. However, the early rollout revealed numerous short-term, startup problems. Worker registration was cumbersome, and payment mechanisms were limited, initially requiring U.S. bank accounts and manual approval. APIs were under-documented, and developers struggled to design effective interfaces. The system also needed better mechanisms for quality assurance and reliability. Another issue was fraud control. Due to these issues, MTurk saw little uptake.

Either out of remarkable patience or bureaucratic indifference, Amazon did not close the service in its first years. MTurk remained a niche tool and far from a commercial breakthrough. Still, it gradually improved.

It took a young professor, Fei-Fei Li, to demonstrate that MTurk could scale to support massive operations. In 2007, Li needed a method for labeling millions of images for what would become ImageNet, a database of images for developing algorithms for image recognition. MTurk unlocked the bottleneck Li had been facing for years. For a time, her project became MTurk’s largest customer.

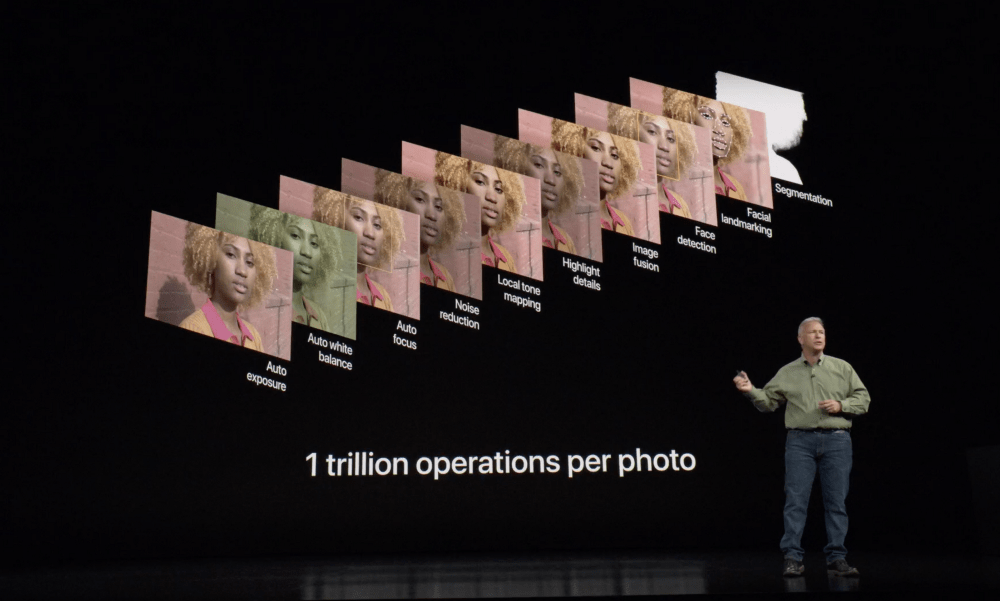

Most of you know how this turned out. Li and her team labeled millions of images and started a contest in 2010. In 2012, AlexNet placed first in the third ImageNet competition. Its Convolutional Neural Network outperformed the competition by a long shot, and the field of algorithms changed dramatically. This technical breakthrough transformed neural networks into the preferred frontier pick-and-shovel for algorithm development.

Trace the line of inventions: Before 2012, image recognition had limited uses, such as handwriting recognition. Among the earliest applications after 2012, neural networks proved valuable for automating camera focus in the iPhone. All the phone cameras use this approach today. In other words, one new pick-and-shovel (in microtasks) helped create another (in algorithm estimation), which improved a widely used product (the smartphone camera), which ultimately helped smartphone camera users.

Note a crucial difference with the experience in integrated circuits. While MTurk continues to thrive today, it cannot stop others from labelling. Data labeling has become its own distinct industry, with many firms specializing in supplying it. MTurk does not dominate labeling the way Qualcomm and Intel did in their respective markets for decades.

More to the point, sectors based on advancing neural networks today are not compensating Amazon for addressing Fei-Fei Li’s bottleneck at a crucial moment. If you make a living estimating algorithms today, remember to thank Amazon.

Conclusion

What do all these pick and shovel suppliers have in common? Believe it or not, they all possess similar incentives to innovate.

Here is what I mean. It took luck and foresight to get to a prominent place. In each case, the firms could control that investment in innovation, but not the luck. For example, Intel invested heavily in R&D to support its exceptional manufacturing record of frontier designs. Qualcomm invested heavily to figure out how to adapt the logic of package switching to wireless communications and offered an integrated chipset to support it. NVIDIA invested heavily in the Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) to support scientific computing, well before it paid off handsomely with the growth of neural networks. Amazon took risks to develop Mechanical Turk. Only in this example, Amazon did not get a handsome payoff.

More generally, the economics of innovation are the same, regardless of distinct managerial issues. When they received payoffs, stockholders benefited from the inventions because the frontier firm made more money from the core invention and subsequent upgrades. Users benefited, as businesses often enhanced their products and sold them to their customers.

Here is the rub. While these inventive investments are unambiguously good for society, the same incentives extend to any action that helps maintain or exploit the monopoly that arises from such inventiveness, implemented at scale. The same incentives also motivate significant investments in the legal defenses and attempts to corner the market for a crucial input, just as Brennan did in his day.

In other words, viewed with a broad perspective, frontier pick-and-shovel markets will necessarily be dramatically inventive, crucial to the economy (eventually), and occasionally exploitative of their users. That also means these firms will be both prominent and, on occasion, necessarily unpopular.

Copyright held by IEEE Micro